IT APPEARS as if Zimbabweans will have to make do with unpredictable lockdowns in one form or the other for the foreseeable future, as the spread of the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which was first detected in China in 2019, continues to mutate and to spread locally.

In this regard, it is commendable that the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare produces and disseminates data on the Covid-19 situation in the country to citizens on a regular basis, including vaccination rates.

On that score too, it is not surprising that the government of Zimbabwe, like other governments around the world, has been grappling with the question of how to reach community immunity, sometimes referred to as herd immunity.

Put differently, every country has been asking the following key question: “How can vaccines reach a critical mass without compulsion?” — particularly in the light of the fact that an employer could demand vaccination as a condition of employees reporting for work, or a university could impose the same requirement on faculty and students.

On the face of it, what seems to be happening a lot in Zimbabwe is the unfortunate incorporation of coercive tactics on the public — farmers and workers present themselves for vaccination without them having full knowledge about what they are taking.

At this point, it is important to emphasise that vaccination is not immunisation, because the two processes are totally different.

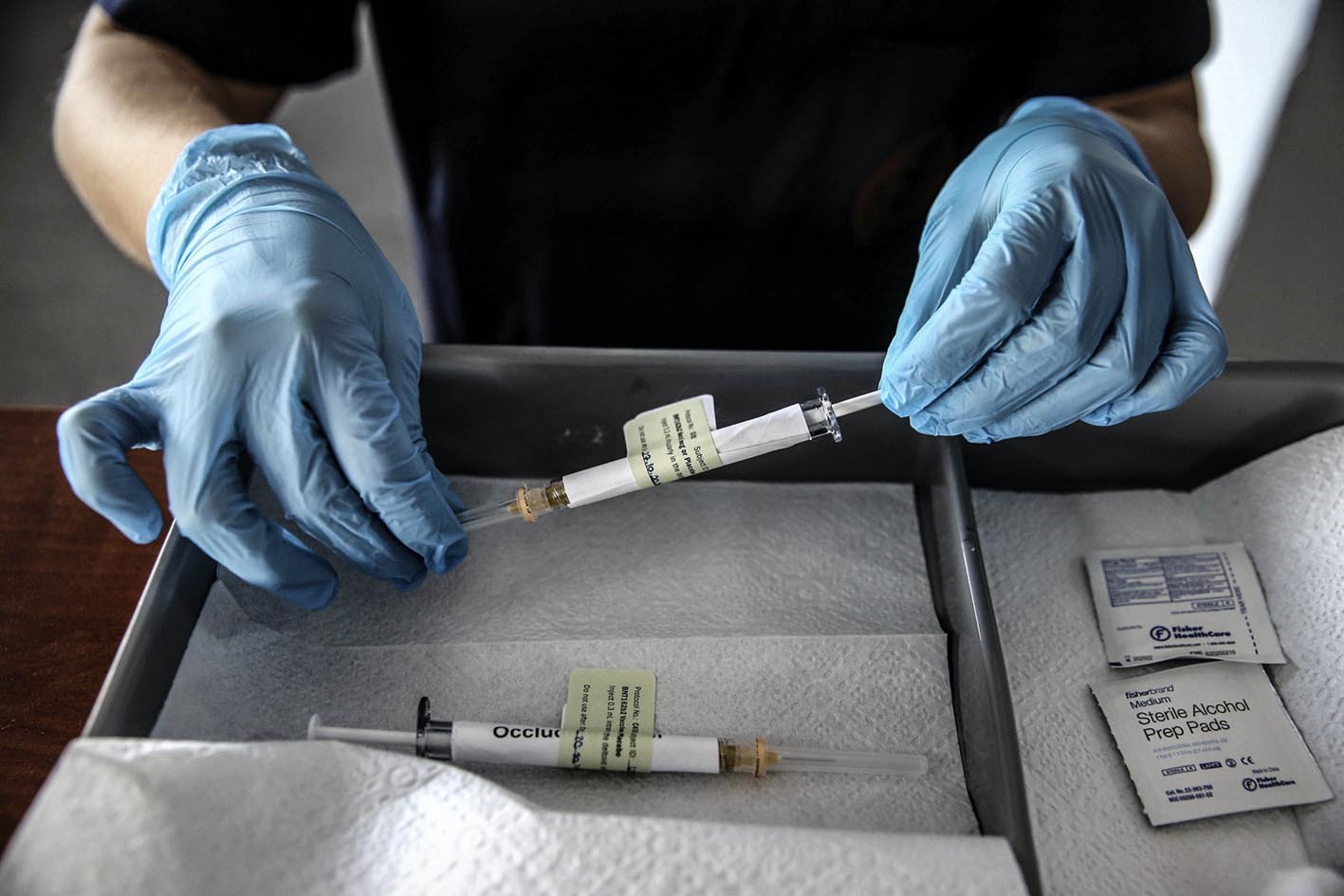

Vaccination is the inoculation of a vaccine in the hope that the person vaccinated will have his or her immune system stimulated to protect them from the infection. In other words, immunisation follows vaccination and it is not a guarantee because it depends on a lot of factors such as the nutritional status of the vaccinee.

It is therefore most unfortunate that this is not well understood by many people, including some healthcare professionals and politicians.

Today, we talk of different types of Covid-19 vaccines that have been developed or are under development by almost 200 companies — all vying for the world market because the coronavirus is here to stay, at least for now. Currently, we have an inactivated virus vaccine, messenger RNA vaccine; a viral vector vaccine and protein-based vaccine.

Many of these were developed using funds from the US, Chinese and European authorities, or from advance purchases of vaccines from companies such as Pfizer. Without such funding, it would not have been possible to move to trials that are currently going on and which we know as “vaccines roll outs”.

Vaccine development is, by its nature, fraught with dangers. For example, the quality of every batch varies during manufacture and, therefore, the effectiveness will also vary. This is because a vaccine can contain different components manufactured at different sites by different companies.

This is notwithstanding the fact that Covid-19 vaccine developers will use any means at their disposal to get their products accepted in spite of the many unknowns. This is also the reason why countries have gone for “Emergency Use Authorisation” (EUA) of vaccines, which does not necessarily mean approval in their respective countries where the manufacturing companies are domiciled.

In Zimbabwe, the equivalent of EUA was done using Section 75 of the Medicines and Allied Substances Act, 15:03 — which has allowed the use of Sinopharm (Chinese), Sinovac (also Chinese), Bharat Biotech (Indian), Sputnik (Russian) and Covishield (British).

In the US, EUA authority allows the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is the equivalent of the local Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ), to help America strengthen the nations’ public health protection. This is done only when the US Secretary of Health (read Minister of Health in Zimbabwe) declares that an EUA is appropriate.

This then authorises the use of unapproved medical products, which means that there still is more information required for eventual approval. The same process is followed in the European Union, through the European Medicines Agency.

If the truth be told then, all vaccines that are being used in the world today have not been approved by any regulatory authority. They are all being tried out to gather the requisite safety, efficacy and quality data in all populations in the world — which is why all companies have indemnified themselves.

In this regard, people should not, therefore, be compelled to be in a clinical trial.

Medical scientists, economists and politicians must all agree that coercion is totally unethical and conscientious objection should be allowed. The moral issues involved should not be viewed either from a euro-centric or afro-centric view point. People should be allowed to make their own informed decisions.

In my considered view, what is needed in Zimbabwe is to make people understand that we are in an emergency situation and that, therefore, vaccination — for now — provides a way out. Thus, the current vaccination rollout is to assist with coming up with useful data for us to deal with the raging Covid-19 pandemic.

Everyone who has been vaccinated should also be encouraged to report any untoward experience following inoculation of whichever vaccine. It should also be made clear by the government, to the vaccine developers, that days of exploiting poor people in Zimbabwe are gone. Indeed, there is no doubt that the companies have responsibility to their shareholders who are not bishops. They are in this game for profit like any other investor.

That being the case, it is important for people to understand the importance of a clinical trial in a situation such as the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. The issue of transparency in all those involved is also paramount.

In the past, vaccines have taken years to develop, for good reasons, and none of the benefits could be realised if they were released before they were deemed safe. It can even be argued that a failed Covid-19 vaccine could compromise confidence in other vaccinations — threatening a return of diseases such as measles and polio.

On that point too, those who conscientiously object to be vaccinated must be encouraged to adhere to all the regulations set out to prevent the virus’ transmission — for example, by wearing a mask in public.

If effort is made by all that this should not be looked at as an infringement of one’s liberty, but an excellent non-pharmaceutical invention it would be wonderful.

Going forward, combined data from vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals will help us understand the biology of the coronavirus. This will also assist in dealing with the moral dilemmas that have been provoked by the development and the distribution of vaccines so far.

Finally, we are now all accustomed to hearing words like vaccine diplomacy, vaccine nationalism and vaccine apartheid in political circles. If everything is transparent at a local level, that should not bother us as Zimbabweans too much.

Our health system is under immense pressure and needs everyone to pull together and assist using a properly developed Covid-19 vulnerability index for Zimbabwe.

* Professor Norman Nyazema is a distinguished academic and pharmacologist. Among many other key roles that he has performed locally, he is a former chairman of the National Medicines and Therapeutics Policy Advisory Committee and deputy chairman of the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe.