Jotted down on paper, this playful story about a lazy lion is now a memento of a young life lost.

Chidera Onovo, 15, was a caring boy who loved to draw and was his mother’s unabashed favourite.

“He saved up his lunch money to buy biscuits to share with his siblings,” Blessing Onovo recalls. “And he was always the one who noticed my moods and would ask: ‘Mummy are you fine?’.”

Last Friday morning Chidera went to secondary school with his younger sister Chisom but only one of them would return.

Official reports from the Nigerian government say 22 students were killed in the building collapse at Saints Academy, a private school in the central city of Jos, but local residents say the number is closer to 50.

Using their bare hands and shovels, parents desperately searched for survivors, managing to tunnel through and free some of the trapped children. “It took about an hour before an excavator came,” says Chidera’s father, Chike Michael Onovo.

“I saw my daughter Chisom being dragged out. I was relieved, but I kept shouting: ‘Where is Chidera my son?’.”

The boy’s body was later found, crushed by the fallen concrete in his classroom on the first floor.

‘People cut corners’

Also searching frantically that day was 43-year-old Victor Dennis. His worst fears were confirmed a day later when he found his son Emmanuel’s lifeless body at a local morgue.

“My boy was a good boy,” he tells the BBC. “He didn’t deserve to die. They killed my son. He didn’t do anything wrong. He just went to school to learn.”

Tears fall from Mr Dennis’ bloodshot eyes as mourners sing a farewell hymn at his son’s burial. Absent is his wife, Emmanuel’s mother, who is inconsolable with grief and stays at home.

People in Jos have rallied to support one another, and many young lives have been saved thanks to blood donors who have visited local hospitals.

But there is anger and disbelief that yet another building collapse has been allowed to happen in Nigeria. Residents even claim the children had felt the building shake the day before.

“Substandard materials were used - these could have been responsible for the collapse of the building,” says regulator and architect Olusegun Godwin Olukoya, who leads the Nigerian Institute of Architects in Plateau state. “Our preliminary investigations indicate that there was possible lack of adherence to building regulations.”

He is scathing in his criticism of builders and the Nigerian authorities, telling the BBC:

“Unfortunately, due to the kind of society that we live in, lack of will has prevent the authorities from adopting our suggestions in the past.

“People cut corners and when you try to raise alarm, some feel that you are trying to victimise or oppress them. They use their people in positions of authority to circumvent the rules.”

Following the building collapse at Saints Academy, the local governor has ordered a structural audit of all schools and public buildings in Plateau state, of which Jos is the capital.

Officials in his government say it is not clear whether the school’s owner, who has since died, ever had a construction permit for the site.

The BBC was unable to get comment from the school’s management.

Some also suspect that mining activity close by could have damaged the school building, so the governor has also ordered the arrest of any artisanal miners found digging in residential areas in the state.

But officials suspect that the main problem was with how the school was built.

“Even as a layman who is not a building professional, you can see that the materials used in the construction are not standard. But we will investigate the cause of the collapse and punish those found culpable,” Musa Ashom, the state Commissioner for Information, tells the BBC.

Similar promises came from Nigeria’s Housing Minister, Ahmed Dangiwa, who spoke scathingly of “unscrupulous” individuals whose actions he said had resulted in the Jos school collapse and caused unquantifiable loss.

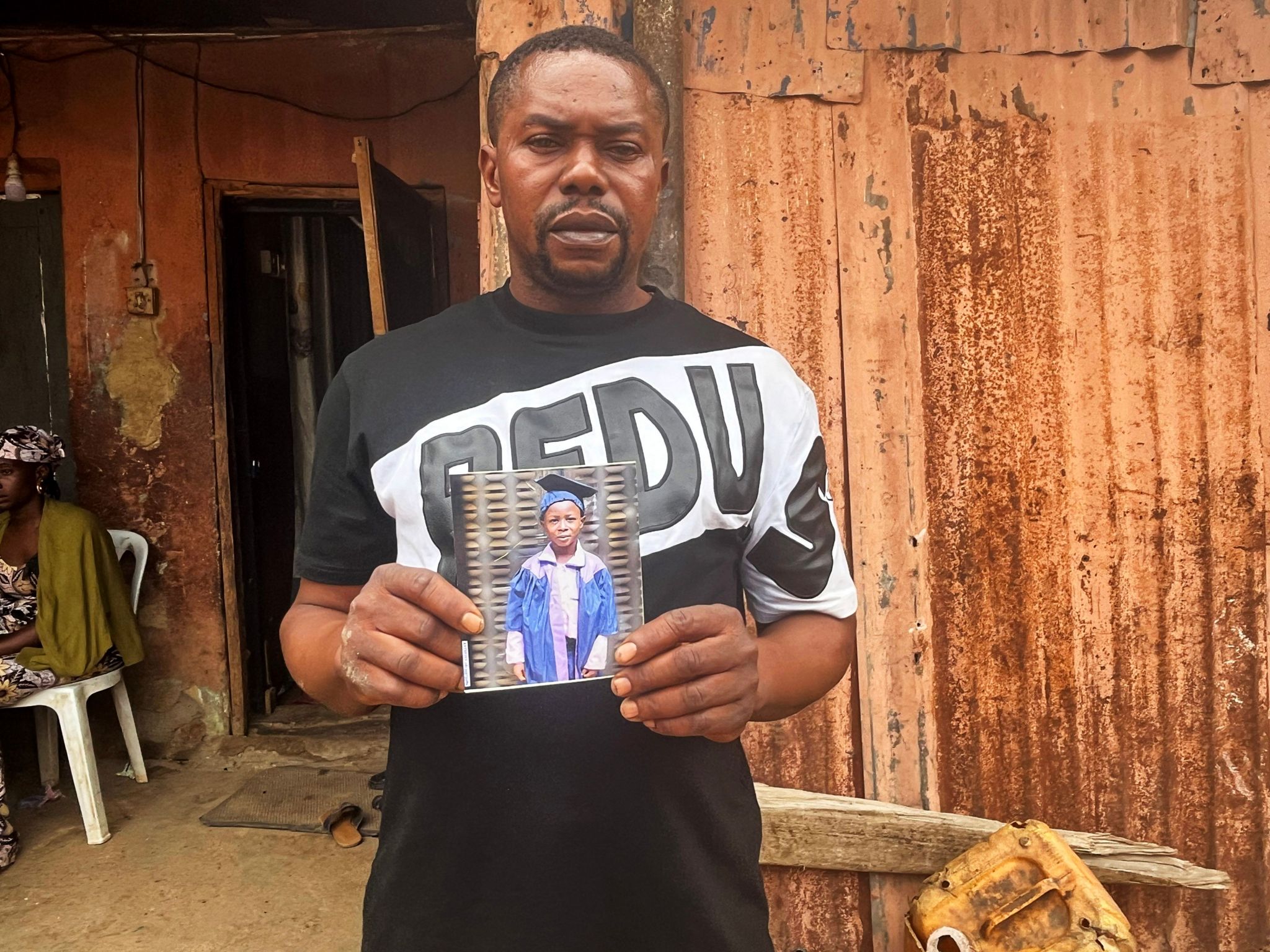

But those words will come as little consolation to the many bereft families, like that of Chinecherem Joy Emeka.

The 13-year-old was one of the best dancers at her school and dreamed of becoming a doctor one day, says her mother Blessing Nwabuchi.

Chinecherem, or Chi Chi as loved ones called her, was sitting her end-of year exams the day she died.

Photos like this one, from her junior high graduation last year, are precious reminders of what she achieved – and everything she might have gone on to become. – BBC

By Chris Ewokor & Ifiokabasi Ettang