THE decision not to renew special visas for Zimbabweans, which granted many nationals of the neighbouring nation the right to do business, work or study in South Africa, is worrying and does not paint South Africa in a good light.

As our columnist Nicole Fritz pointed out, it comes at a time when South Africa has found itself in the hands of disgraceful treatment from the UK and other countries who have locked us out of travel due to the Omicron variant of Covid-19. President Cyril Ramaphosa has rightly taken umbrage at other African countries who joined the ban, saying they show a lack of solidarity.

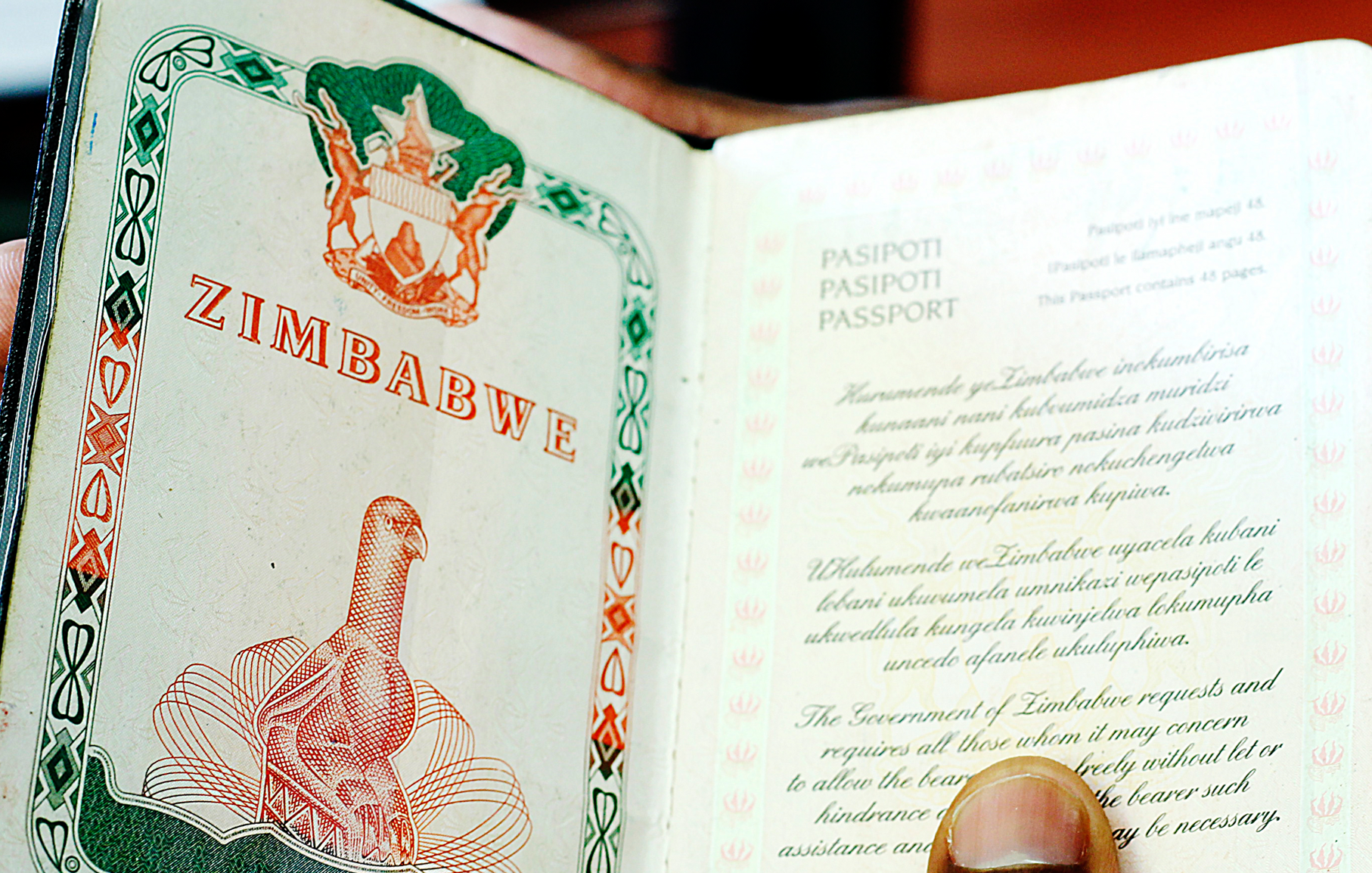

But what about solidarity with the close to 200 000 Zimbabweans who had qualified for the special visas — teachers, farm labourers, spaza shopkeepers and e-hailing taxi drivers — and who have since made South Africa their home, rebuilt their lives here and started families? The visas were first introduced in 2009 to allow Zimbabweans working illegally in South Africa to gain legal status. Many had fled as the Robert Mugabe regime wreaked havoc, leading to political turmoil and economic collapse. The move by the South Africa government to grant the visas for an initial five-year period, which was extended twice to provide a lifeline to Zimbabweans, was largely seen as a gesture of goodwill and many expected their right to stay would be indefinite.

But without much warning, the government has now told them to go home at a time when Zimbabwe’s economy under Emmerson Mnangagwa has completely collapsed and the political tension and civil unrest persist.

Admittedly, it is not South Africa’s responsibility to carry Zimbabwe’s burdens. However, as the region’s most influential state, South Africa is required to show moral leadership. Having extended the Zimbabwean special permits twice before, the South Africa government was clearly cognisant of the reality that its northern neighbour was not out of the woods. So what has changed now?

It is sad that the decision, weeks after the ruling ANC suffered losses in local government elections, gives the impression the government has succumbed to anti-immigrant sentiment, which has often led to violence. This hostility comes despite any evidence that foreigners are to blame for crime or a lack of jobs. In fact, studies, including by the World Bank, have shown that immigration can accelerate job creation. The reason the South Africa economy has stagnated or contracted in the past decade is not because of the presence of immigrants.

Minister in the presidency Mondli Gungubele said while the visas will expire on December 31, holders are to be given a 12-month grace period to apply for other permits they may qualify for, which means they have until the end of 2022 to sort out their paperwork.

He obviously has not gone to a home affairs office recently, otherwise he would be well aware of their dismal “service” levels — those affected will have virtually no chance of their situation getting resolved. It is further evidence of how out of touch our politicians are. An additional problem is that many of those affected probably do not qualify for any other permit.

After its dismal showing in the November local government elections, the ANC government seems to be looking for easy political points instead of focusing on bigger issues such as economic growth and political stability across the continent, which is necessary to create a stable and prosperous region.

The decision is a missed opportunity for South Africa to show moral leadership and ubuntu, a philosophy that calls for compassion. But more importantly, South Africa had more to gain than lose by renewing the permits. It could then have used its increased moral authority to push for broader political reforms in troubled countries in the region, not least Zimbabwe and Eswatini.

Nobody is advocating a chaotic open-border policy, but to pull the rug from under people who had a reasonable belief that they had done enough to ensure their legal status cannot be morally justified.

— Business Day