By Adelaide Moyo

FORTY-five-year-old Chinjai Chikore (not his real name) had hardly contemplated leaving Kanyandura Village in rural Mashonaland East province’s Mudzi district; not until just recently when a Chinese miner indicated that it needed to move into his village to prospect for and mine lithium.

He was born here and grew up tending the family livestock and cultivating the household plot, just like any other child.

His parents, grandparents and great grandparents lived in the same area. They were spared the forced evictions that came with colonialism that started in the late 1890s and ended with black rule in 1980.

Changing times

But the situation is changing quickly. Chikore and his family whose identities are being protected out of fear of victimisation, could soon be trekking out of the place they have known as home for more than a century.

And the future is uncertain because they do not have a clue where they could be headed for.

They face a curse that is now common one Zimbabwe. They have to make way for commercial interests as foreign and local investors advance on this province that is rich in black granite, lithium and gold, among other natural endowments.

His story mirrors that of many villagers of Kanyandura Village in Mudzi Ward 5, surrounding communities and neighbouring rural districts who are facing displacements as Chinese miners exploit the areas for minerals.

China which has strong historical ties with the southern African nation has been one of the most preferred investors after Zimbabwe faced international isolation.

Chinjai is one of several villagers who have been left disgruntled due to the exploitation and mining of lithium, granite and gold by investors in Mudzi and Mutoko districts in the province.

“What has been happening is unfair because we can’t connect with our ancestors when they displace us,” Chinjai said.

Already, three families in Nyamakope in Mutoko have been moved by Jinding Mining Zimbabwe, a Chinese granite mining company based in the area.

Villagers from this province that is dominated by the ruling Zanu PF party are mostly reticent to air out their grievances—particularly ahead of an election like the 2023 general polls to be conducted in August.

However, once you earn their trust, they can easily open up.

Taken over

Information for Development Trust (IDT), a non-profit media organisation supporting investigative journalism, convened a dialogue in Nyamutsahuni, an area in Mutoko, in mid-2022, where villagers openly complained that the same company, Jinding, was encroaching their fields and pastures, driving hunger up.

Villagers who attended the meeting accused the company of diverting the river course where they used to draw water for domestic use and reneging on its promise to drill boreholes for them.

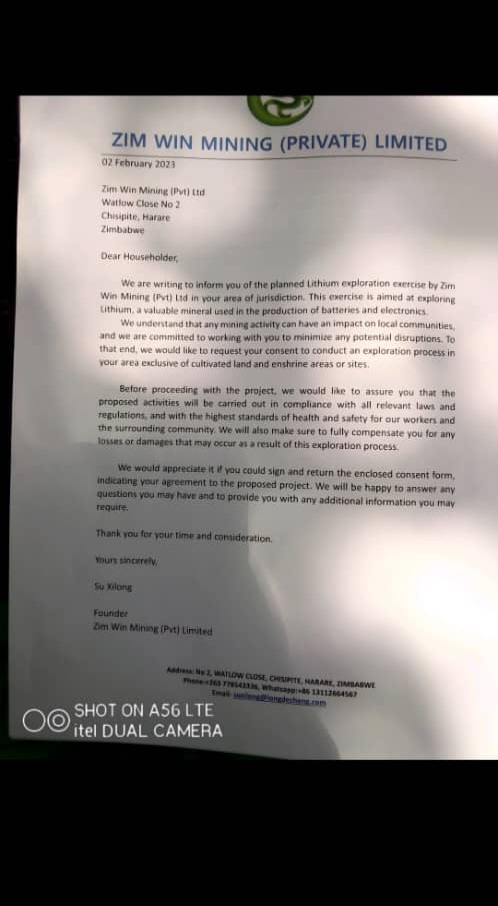

Another Chinese firm, Zim Win Mining recently wrote to households in Mudzi’s Ward 5, informing them of its plan to use part of the land in the area for lithium exploration and mining.

At another dialogue organised by IDT early this year, the villagers accused Zim Win of trying to cheat them out of their land by making them sign consent forms that would have given the company the authority to remove them from their land to make way for a lithium extraction project.

According to investigations supported by IDT, the consent form is not clear on how the villagers would be compensated. Nor does it specify its relocation plan.

“We understand that any mining activity can have an impact on local communities, and we are committed to working with you to minimise any potential disruptions. To this end, we would like to request your consent to conduct an exploration process in your area exclusive of cultivated land and enshrine areas or sites,” a letter by Zim Win founder, Su Xilong dated February 2 reads.

Under the Mines and Minerals Act, a prospecting company is supposed to consult the local authority, the rural district council in this case, and the affected people, but villagers who spoke at the dialogue said none of that happened.

Section 31 (h) of the Mines and Minerals Act states that no prospecting can take place “upon any communal land occupied as a village without the written consent of the rural district council established for the area concerned.”

An environmental expert working under the council also said that they had not been consulted, indicating that Zim Win was attempting to prospect for lithium illegally.

Kudakwashe Makanda, the programmes officer for the Mutoko-based Youth Initiative for Community Development which helped IDT organise both dialogues said there was no fair compensation of villagers who would have been displaced.

Weakened

“The sad thing is that when the displacements happen, there isn’t a resettlement plan and consultation of those that are being displaced. Additionally, because of the poverty that our people are suffering, their bargaining power is limited.

“Victims of displacements are usually short-changed because they have little understanding of the process and, in some cases, they get the chance to ask for compensation but under-state the value of their assets,” Makanda said.

Villagers have often been evicted from their land without recourse to the courts as the law requires.

Section 74 of the Zimbabwe Constitution stipulates: “No person may be evicted from their home, or have their home demolished, without an order of court made after considering all the relevant circumstances.”

But the laws contradict themselves and there have been calls to align all the statutes and regulations relating to land ownership and minerals.

Zimbabwe is still using the Communal Lands Act (1981), which mirrors the 1951 Native Land Husbandry Act that deprived indigenous people of their right to land and vests ownership in the president, who can arbitrarily move communities from their ancestral land.

Simbarashe Machiridza, a legal expert, urged relevant authorities that include the Mines ministry officials and the investors to clearly disclose compensation terms for improvements on communal land when evicting people.

“The villagers can approach the court to challenge their displacement either on the basis that their displacement is not in the community’s interest or that they have not been adequately compensated. However, in these circumstances, we have to be alive to the fact that communal land is vested in the president and therefore occupation and use are at his pleasure,” Machiridza said.

“It’s proper that the process be done in an open manner with all key stakeholders being involved including traditional leaders, community leaders, government among others. This would avoid a situation when the process is done in a manner that takes advantage of community members who might not fully appreciate the terms,” he added.

An official working at the Mudzi Rural District Council bemoaned the circumventing of the local authority.

“We encourage the investor to engage the local leadership including the local communities where the mining actually takes place,” the official said.

Sidestepping the leaders

The Zanu PF councillor for Ward 5 in rural Mudzi where Zim Win is pushing to prospect for lithium told delegates at the IDT-organised meeting that foreign investors were sidestepping them.

“The Chinese are coming into our area but they are not following the proper procedures and laws applicable in our area for us as communities to work amicably with them. Sometimes they come and just start their activities.

“There should be a law to address this and also enforce compliance so that they can do their mining activities properly. They do not recognise the traditional leaders, neither do they recognise us councillors and headman as local leaders,” Saineti said.

The Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG) director, Farai Maguwu, said communities in Mutoko and Mudzi were in distress due to the pending displacements in the area.

“We have visited some of the communities and all I can say is the villagers are distressed. They are living in fear and there is uncertainty about the future,” said Maguwu.

He is concerned that government authorities are restricting the operations of civil society organisations coming from outside the province.

“There is no room for civil society intervention. You can easily see the fear on people’s faces when they talk to you. The traditional leaders are helpless as foreign companies render villagers homeless,” he added.

The country has experienced an increased interest in lithium mining activities which has seen an influx of investors and projects.

Lithium is a vital raw material required in the transition to a green economy, and the country is seeking to capitalise on the global drive towards renewable energy to rake in foreign currency.

“It seems that the discovery of lithium is not going to benefit us as we get robbed of our natural wealth and left worse off,” said a Mutoko villager.

The Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (Zela) is worried that, amid the lithium frenzy, authorities are neglecting the economic, social, environmental, and human rights implications associated with its mining.

“The government should develop relocation and compensation guidelines which involve all affected parties for investors to follow as they consider relocating communities to pave way for lithium mining,” Zela stated in a recent report titled “Implications of the Lithium Mining Rush in Zimbabwe”.

In Zimbabwe, lithium is expected to rake in US$500 million under the U$12 billion mining economy target set by government in 2019.

*This article was produced in partnership with the Africa-China Reporting Project (ACRP)