EDUCATION reentry or continuation policies for pregnant schoolgirls, while still controversial in some contexts, have gone a long way towards securing their right to remain in school.

Where effectively implemented, the measures have helped girls build their careers, edging them closer to a more secure, economically empowered future.

These are girls who would otherwise have been struck off the school register at the point of their teen pregnancies, contradicting eff orts to “leave no one behind”, whereas the male partners in the pregnancies continue their education and build their careers.

Although these measures are invaluable to ensure girls’ right to education during and after pregnancy, they must be complemented by sexual and reproductive health education, encouraging girls to prioritise completing their secondary school education and their health by delaying their sexual debut.

This benefits their decisionmaking capacity and typically leads to better life choices. In 2021, Human Rights Watch noted that at least 30 countries in Africa had measures to protect pregnant students’ and adolescent mothers’ right to education to varying degrees.

But some countries still have policies that are discriminatory and bar pregnant girls and teenage mothers from going to school. The implementation of these policies provides insights for a review of the structural changes needed to strengthen their eff ectiveness.

Zimbabwe, for instance, revised its Education Act in 2019 to include no discrimination based on pregnancy. According to researchers Theresa Takafuma and Rutendo Chirume, in an article published last month, progress has been slow and more needs to be done.

Zimbabwe is among the countries in sub-Saharan Africa with a high rate of teenage pregnancies, according to Education International, a global union federation of teachers’ trade unions. In 2020 it recorded more than 6 000 girls who became pregnant during the first wave of Covid-19, when schools closed for more than three months. In January last year, nearly 5 000 girls were pregnant. Furthermore, the Covid-19 school closures left many learners vulnerable. Once out of school, these teenage mothers have to find domestic work to support their children, with some condemned to child marriage, because they are forced to live with the men responsible for the pregnancy.

The poor implementation of return-to-school policies has resulted in many pregnant girls dropping out. In interviews with girls, some teachers, family and community members, for Africa in Fact, Good Governance Africa’s quarterly publication, respondents said that despite enabling laws, pregnancy itself can threaten girls’ health, because often they are physiologically too immature to carry a pregnancy and deliver a baby without life-threatening complications.

Adolescent maternal mortality is a global concern, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) noting that complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death for girls aged 15 to 19 years globally.

The WHO further notes that: “Of the estimated 5.6-million abortions that occur each year among adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 years, 3.9-million are unsafe, contributing to maternal mortality, morbidity, and lasting health problems. Adolescent mothers (ages 10 to 19 years) face higher risks of eclampsia, puerperal endometritis, and systemic infections than women aged 20 to 24 years, and babies of adolescent mothers face higher risks of low birth weight, premature delivery, and severe neonatal conditions.”

Clearly, adolescent or teen pregnancy presents a new layer of health difficulties for girls, some already vulnerable to poverty. Separate interviews with senior women teachers (who requested anonymity) from Bulawayo, Inyathi, Shurugwi and Marondera in Zimbabwe confirm this.

“The policy only exists on paper,” one teacher said. “Once learners leave the school system due to pregnancy, only a few return to write their examinations, as they experience a new layer of abuse, even by the teachers.

Some girls have had to endure endless summons by women teachers, who not only subject them to intrusive questions, but sometimes ask the learners to display, and even request to touch, their protruding stomachs.”

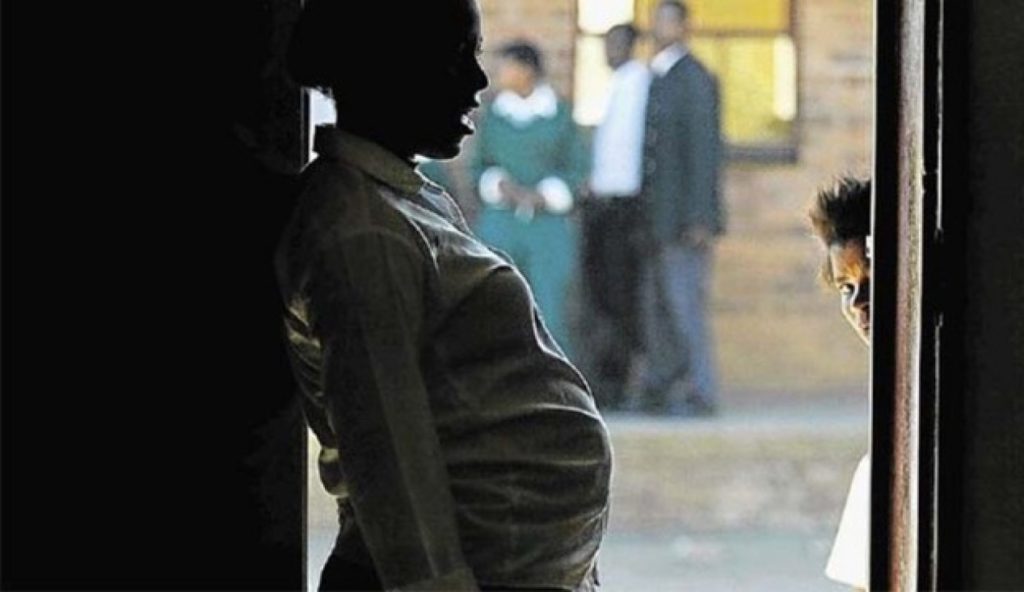

This additional layer of problems was also highlighted by Rosa (not her real name). She told Africa in Fact that in 2014, aged 17, she became pregnant, and had to endure the stigma of being “a pregnant learner in uniform”, something perceived as a moral contradiction.

This was before the Education Amendment Act, which states that “no child shall be excluded from school based on pregnancy”. Rosa acknowledged the importance of this law, saying that she quit school during pregnancy and only returned after giving birth. She said that one of the immediate problems is the ostracisation fuelled by the gossip among family, community, colleagues and even school authorities.

Most girls cannot cope, resulting in some quitting school and going off to get married, she said. “Maybe some girls have been lucky, but once known to be pregnant, the stigma is unbearable.” Rosa said she was in the second term of her form three studies when she became pregnant, and re-entered school two years later: “I still felt a desire to complete my education like my peers, but, importantly, now realised the need for a career that would enable me to provide for my child.

By being afforded another chance, I was able to catch up on my learning. But I was only able to do so because my mother was there to provide good care for my daughter.” Measures that help girls complete school can deliver significant career-building and economic empowerment benefits. But, as Rosa noted, unless one gets suffi cient counselling and family support, it’s not always an easy journey. — Africa in Fact